As the Appalachian Trail wound down Mt. Guyot to Crawford Notch, it took me past the Zealand Fall Shelter to beautiful Ethan Pond where I spent the night. Rain made the hike a dreary slog, but the next morning cleared and I descended to the Notch that had once been a magnet for travelers and tourists seeking mountain relief from the summer heat of Boston and other cities to the south. The first transcontinental automobile road, The Theodore Roosevelt International Highway (now #302), went through Crawford Notch. In the early years of the twentieth century, the area boasted four Grand Hotels. Even in 1967, the Notch was still active with tourists, but the splendor of an earlier era had long vanished.

As the Appalachian Trail wound down Mt. Guyot to Crawford Notch, it took me past the Zealand Fall Shelter to beautiful Ethan Pond where I spent the night. Rain made the hike a dreary slog, but the next morning cleared and I descended to the Notch that had once been a magnet for travelers and tourists seeking mountain relief from the summer heat of Boston and other cities to the south. The first transcontinental automobile road, The Theodore Roosevelt International Highway (now #302), went through Crawford Notch. In the early years of the twentieth century, the area boasted four Grand Hotels. Even in 1967, the Notch was still active with tourists, but the splendor of an earlier era had long vanished.

After crossing Route 302, the trail takes on a new character. It ascends the walls of Webster Cliffs on switchbacks. The exposure is moderate, but as you rise above the Notch, you enter a new world: the southern Presidentials, a prominent range of mountains named for American presidents that is notorious for having some of the worst weather on earth. Its high winds can produce winter-like conditions even in summer.

I crossed Mt. Jackson with its rocky top and pushed on through the low-lying pines to Mt. Pierce (also known as Mt. Clinton) that provides some good views far to the north of Mt. Washington, the tallest of the range at 6,288 feet, and its weather and radio towers.

Shortly after descending Mt. Pierce, the trail rises again above tree line and remains in the open over the next eleven miles of the rock and bolder strewn Presidential Range.

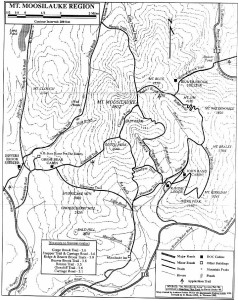

I spent the night at Lake of the Clouds Shelter near Mt. Washington where I heard rumors of an off trail shack on the edge of King Ravine on Mt. Adams. Later I would learn that the shack was Crag Camp. It had been privately constructed at a dramatic 4,200 feet in 1909 – the last of the high cabins – and was taken over in the 1930s by the Randolph Mountain Club. I was told that the camp could be accessed by the Spur Trail at Thunderstorm Junction below Mt. Adams.

![Crag Camp 1965 [Photo: Chris Goetze; Scan "Crag65d" provided to the RMC Archive Aug 2003 by Lydia Goetze, who owns the original photo.] Crag Camp, 1965 Photo by Chris Goetze](https://gettingtoknowjesus.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/cragcamp1965-300x229.jpg) My ankle had been acting up, so I decided to detour off the main route and descend to the Crag. I arrived in the rain. When I pushed opened the creaky door, I entered a hazy blur of people and smoke. All eyes turned to me as I tried to decide whether this was a vision of paradise or something more ominous. Then someone said, “Come on in and close the door.” I did as instructed and entered a world of camaraderie and warmth that came to represent everything I treasure about the trail.

My ankle had been acting up, so I decided to detour off the main route and descend to the Crag. I arrived in the rain. When I pushed opened the creaky door, I entered a hazy blur of people and smoke. All eyes turned to me as I tried to decide whether this was a vision of paradise or something more ominous. Then someone said, “Come on in and close the door.” I did as instructed and entered a world of camaraderie and warmth that came to represent everything I treasure about the trail.

The difference between normal life and trail life is that on the trail everything is compressed. In our everyday existence, time is elastic; it can seem to stretch on forever, but on the trail, time is a stern companion. You track when the sun rises and sets and live consciously by the cycle of each day. Hikers delight in fair weather but struggle under blasts of pelting rain and gusting wind. As the environment changes, so do your companions: they appear and disappear with regularity. We may have our own agenda, but nature and the trail are the ultimate schedulers.

My stay at Crag Camp lasted two nights. I left behind nameless friends and powerful memories but I had to push on. I climbed back up to Thunderstorm Junction, hiked up the rocky side of Mt. Adams and then over Mt. Madison before descending to Pinkham Notch and the long journey back to my future. But the memory of Crag Camp lives on. In fact, I could not stay away. I returned to Crag with my son Alex in 1995; two years before, the old cabin had been torn down and replaced by a very different version of the camp. It still rested spectacularly on the edge of King Ravine, but the new building was nothing like the ramshackle cabin I remembered from 1967. In most ways it was much better – by AT standards the cooking, dining and sleeping facilities are now luxurious – but even so, the memory of those few days at old Crag keeps me coming back again and again.

The Randolph Mountain Club’s video introduction to Crag Camp today.